Bewitched

I recently spent three months as composer-in-residence to the stroke unit of a major Dublin hospital and can honestly say it was one of the most fascinating and rewarding experiences of my professional career. Part of the project involved the group of musicians for which I was writing an ‘outcome’ work (titled ‘Bewitched’) coming into the hospital every fortnight to give an open rehearsal of the latest movement as part of an hour-long performance of light and popular pieces to an audience of patients. After the first such session it really hit home that, for possibly the first time in my life, I was writing for a very specific audience, consisting of mostly quite elderly and infirm people who were not by any stretch of the imagination regular concert-goers. This necessitated a conceptual change of tack on my part as I realised I couldn’t just write any old abstract Modernist work(!) which had no connection whatsoever to the context, musical or otherwise, of the people who would be listening to the piece as it took shape over the weeks.

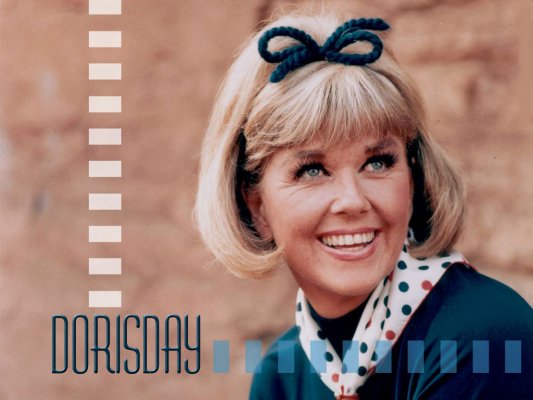

As luck would have it, I had very early on in the project sat in on a group physiotherapy session at which, playing throughout in the background, was a CD of music by singers the patients had grown up with, namely Doris Day and the Rat Pack. A light bulb went off in my head and I decided that segue-ing into a Doris Day song at the end of each one of my ‘songs’ (based on interviews I was making with patients, doctors and other healthcare workers) would not only provide a link with the musical experience of my audience but, if approached in the right way, could also illuminate my own music in a very interesting and, hopefully, moving way.

For instance, the very first movement is based on an interview with a young mother of thirty who suffered a stroke two weeks after giving birth to her first child and she related how she had initially been very scared as she had briefly lost her ability to speak. I also interviewed her husband who was doing a brave job of holding everything together and the bond between them was clear. When I interviewed her, a week after first meeting her, she had improved enormously and was going home that very day. However, in her interview she described beautifully her fear and confusion just after her stroke and I was able to move from my musical setting of that description into the song ‘Fly me to the moon’, with its intimations of fantasy, escape and romance, which seemed a very suitable and powerful contrast with what she had described.

Another movement is based on a speech therapy session I sat in on where the patient had been severely affected by stroke and had no speech and impaired cognition. The conversation was therefore one-sided but the therapist was so supportive and understanding that her words, which were spoken in short sentences (“What do you do with this?”, “Can you tell me?”, “Yes, that’s it!”), give a clear idea of the frustration the patient must have been experiencing. When I set these phrases to music I was able to set them exactly as they had been spoken, rhythmically and melodically, which was actually the only instance where I did this. I segued that text into the song ‘Secret Love’, and the effect is quite difficult to describe in words as there are a number of possible interpretations of why I chose this – for me, though, it is describing an aspiration for what the patient would presumably wish for herself and what those around her would wish for her: “Now I sing it from the highest hills” – the power to be heard and understood.

The final movement is a setting of a quite matter-of-fact conversation with a patient who had been mildly affected by stroke but who nevertheless was feeling – quite understandably – rather sad that his life had taken this turn: “I’m still trying to come to terms with it”, he told me; “I suppose I now have to get used to the idea that everything isn’t as good as it would have been”. These are the last words I set in the work and the movement then morphs into the song ‘Bewitched’, which begins with the line “I’m wild again, beguiled again, a simpering, whimpering child again – bewitched, bothered and bewildered am I”. This is actually a striking description of what stroke can do to people, as if like a spell has been cast, and depending on the patient the effects can bewilder or, in more extreme cases, reduce the person to a child-like dependency on others.

While the use of existing songs was not my original plan, I feel that my decision to do so was directly influenced by the patients who heard the work unfold over the weeks, and I am glad it turned out this way because I believe the work makes a much stronger impact as a result of its juxtaposition of these elements. That it made such a positive impact on its (very specific) audience convinced me that, on certain occasions at least, the notion of writing only for oneself is not always the best option.