His Life Overview:

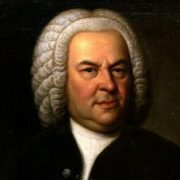

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827), the second-oldest child of the court musician and tenor singer Johann van Beethoven, was born in Bonn. Ludwig’s father drilled him thoroughly with the ambition of showcasing him as a child prodigy. Ludwig gave his first public performance as a pianist when he was eight years old. At the age of eleven he received the necessary systematic training in piano performance and composition from Christian Gottlob Neefe, organist and court musician in Bonn. Employed as a musician in Bonn court orchestra since 1787, Beethoven was granted a paid leave of absence in the early part of 1787 to study in Vienna under Mozart. he was soon compelled to return to Bonn, however, and after his mother’s death had to look after the family.

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827), the second-oldest child of the court musician and tenor singer Johann van Beethoven, was born in Bonn. Ludwig’s father drilled him thoroughly with the ambition of showcasing him as a child prodigy. Ludwig gave his first public performance as a pianist when he was eight years old. At the age of eleven he received the necessary systematic training in piano performance and composition from Christian Gottlob Neefe, organist and court musician in Bonn. Employed as a musician in Bonn court orchestra since 1787, Beethoven was granted a paid leave of absence in the early part of 1787 to study in Vienna under Mozart. he was soon compelled to return to Bonn, however, and after his mother’s death had to look after the family.

In 1792 he chose Vienna as his new residence and took lessons from Haydn, Albrechtsberger, Schenck and Salieri. By 1795 he had earned a name for himself as a pianist of great fantasy and verve, admired in particular for his brilliant improvisations. Before long he was traveling in the circles of the nobility. They offered Beethoven their patronage, and the composer dedicated his works to them in return. By 1809 his patrons provided him with an annuity which enabled him to live as a freelance composer without financial worries. Beethoven was acutely interested in the development of the piano. He kept close contact with the leading piano building firms in Vienna and London and thus helped pave the way for the modern concert grand piano.

Around the year 1798 Beethoven noticed that he was suffering from a hearing disorder. He withdrew into increasing seclusion for the public and from his few friends and was eventually left completely deaf. By 1820 he was able to communicate with visitors and trusted friends only in writing, availing himself of “conversation notebooks”.

The final years in the life of the restless bachelor (he changed living quarters no fewer than fifty-two times) were darkened by severe illness and by the struggle over the guardianship of his nephew Karl, upon whom he poured his solicitude, jealousy, expectations and threats in an effort to shape the boy according to his wishes. When the most famous composer of the age died, about thirty thousand mourners and curious onlookers were present at the funeral procession on March 26, 1827.

Beethoven’s Childhood:

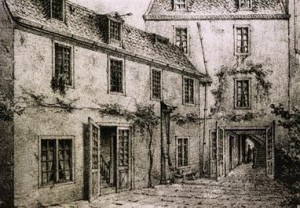

Beethoven was born in this house, at 515 Bonngasse, Bonn, on 17 December 1770. This pencil drawing was made in 1889 by R.Beissel, 58 years after the death of the composer.

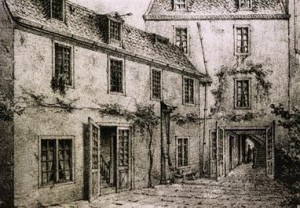

Beethoven was born in this house, at 515 Bonngasse, Bonn, on 17 December 1770. This pencil drawing was made in 1889 by R.Beissel, 58 years after the death of the composer.

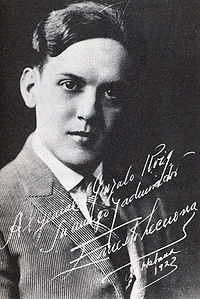

For someone who was destined to be lionized by the aristocracy of his time, Beethoven’s start in life was inauspicious. He was born in Bonn in 1770, the son of an obscure tenor singer in the employ of the Elector of Cologne. Though the exact date of his birth is not known, it is known that Beethoven was baptized on December 17, 1770. It was customary for people to be baptized the day after they were born and indeed it is known that his family celebrated his birthday on December 16th. There is also some debate in the field centering around the fact that Beethoven told people he was born in 1772 and that it was his older brother Ludwig Maria was was born in 1770. However, Ludwig Maria is believed to have been baptized in 1769. Some scholars believe that Beethoven’s farther tried to move Beethoven’s birth year to 1772 in order make him younger and there more of a musical prodigy. In the end Beethoven most probably born on December 16, 1770. His father was said to be a violent and intemperate man, who returned home late at night much worse for drink and dragged young Ludwig from his bed in order to “beat” music lessons into the boy’s sleepy head. There are also stories of his father forcing him to play his violin for the amusement of his drinking cronies. Despite these and other abuses – which might well have persuaded as lesser person to loathe the subject – the young Beethoven developed a sensitivity and vision for music.

When, despite his father’s brutal teaching methods, Ludwig began to show signs of promise, other teachers were called in. By the age of seven he was advanced enough to appear in public. A year or so later the composer Christian Gottlob Neefe took over his musical training and progress thereafter was rapid. Ch. G. Neefe introduced Beethoven to the works of Bach and Mozart. Beethoven must have felt immense pride when his Nine Variations for piano in C minor were published, and was listed later in a prominent Leipzig catalogue as the work of ‘Louis van Betthoven (sic), aged ten’. (The former is an intentional misspelling)

In 1787, Beethoven went to Vienna, a noted musical center, where then Count Waldstein engaged Beethoven was piano teacher and became his friend and patron. Beethoven must have felt a little out of his depth for he was clumsy and stocky; his manners were loutish, his black hair unruly and he habitually wore an expression of surliness on his swarthy face. It was here that Beethoven met the great Mozart, who was dapper and sophisticated. He received the boy doubtfully, but once Beethoven started playing the piano his talent was evident. “Watch this lad,” Mozart reported. “Some day he will force the world to talk about him.”

The death of Beethoven’s mother in the summer of 1787 brought him back to Bonn.

Beethoven’s Ascent to Greatness:

With the death of Beethoven’s mother, the last steadying influence on Beethoven’s father was removed. The old singer unhesitatingly put the bottle before Ludwig, his two younger brothers, and his one-year-old sister. The situation became so bad that by 1789 Beethoven was forced to show the mettle that was to stand him in good stead later in life. He went resolutely to his father’s employer and demanded – and got – half his father’s salary so that the family could be provided for; his father could drink away the rest. In 1792 the old man died. No great grief was felt: as his employer put it, “That will deplete the revenue from liquor excise.”

For four years Ludwig supported the family. He also made some good friends, among them Stephan von Breuning, who became a friend for life, and Doctor Franz Wegeler, who wrote one of the first biographies of Beethoven. Also, Count Ferdinand von Waldstein entered Beethoven’s circle and received the dedication of a famous piano sonata in 1804.

In July 1792 the renowned composer Haydn passed through Bonn on his way to Vienna. He met Beethoven and was impressed, and perhaps disturbed, by his work. Clearly, he felt, this young man’s talents needed to be controlled before it could be developed. Consequently Beethoven left Bonn for good early in November 1792 to study composition with Haydn in Vienna. However, if Haydn had hoped to “control” Beethoven’s talent he was fighting a losing battle. Beethoven’s music strode towards the next century, heavily influenced by the strenuous political and social tensions that ravaged Europe in the wake of the French Revolution. Haydn, who had been a musical trend setter himself in youth, found that Beethoven was advancing implacably along the same radical path. After realizing that Haydn was not the master he was looking for, Beethoven moved onto Albrechtsberger, another prestigious musician who called him an “excited musical free-thinker”.

Those first weeks in Vienna were hard for Beethoven. Opportunities were not forthcoming; expectations were unfulfilled. In addition it must have irked him, fired as he was by the current spirit of equality, to have to live in a tiny garret in Prince Lichnowsky’s mansion. Soon, however, the Prince gave him more spacious accommodation on the ground floor, and, mindful of the young man’s impetuous behavior, instructed the servants that Beethoven’s bell was to be answered even before the Prince’s own!

Impetuosity was also a feature of his piano playing at this time. In those days pianists were pitted against each other in front of audiences to decide who could play more brilliantly and improvise the more imaginatively. Beethoven’s rivals always retired, bloodied, from such combat. While he made enemies of many pianists in Vienna, the nobility flocked to hear him. Personally and professionally his future looked bright. Compositions poured from him and he gave concerts in Vienna as well as Berlin, Prague, and other important centers. His finances were secure enough for him to set up his own apartments. He was the first composer to become a freelance by choice, as opposed to depending on patrons. However, it was his skill as a pianist rather than as a composer that brought him recognition during his twenties. He was one of Vienna’s dominant music personalities surrounded by aristocrats and famous musicians. Until the coming of his deafness, he had five principle resources: Pianoforte Playing, Teaching, Composition, Dedications, and Concert-giving.

The first concert of his own responsibility occurred on April 2, 1800 he launched his first Symphony and introduced his world famous Septet op. 20. One year later, however, in 1801 his deafness began to hit Beethoven, causing great turmoil in his life.

Beethoven Demeanor:

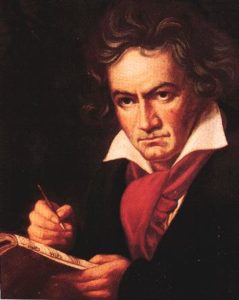

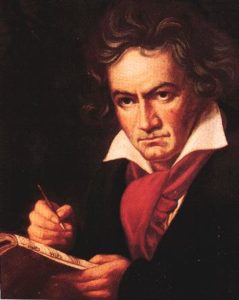

The mature Beethoven was a short, well build man. His dark grey hair, then white, but was always thick and unruly. Reports differ as to the color of this eyes. His skin was pock-marked and his mouth, which had been a little petulant in youth, later became fixed in a grim, down-curving line, as if in a permanent expression of truculent determination. He seldom took care of his appearance, and, as he strode through the streets of Vienna with hair escaping from beneath his top hat, his hands clasped behind his back and his coat cross-buttoned he was the picture of eccentricity. His moods changed constantly, keeping his acquaintances guessing. They could never be sure that a chance remark might be misconstrued or displease the master in some way, for his powerful will would admit of no alternative view once he had made a judgment.

By nature, Beethoven was impatient, impulsive, unreasonable and intolerant; deafness added suspicion and paranoia to these attributes. He would often misunderstand the meaning of a facial expression and accuse faithful friends of disloyalty or conspiracy. He would fly into a rage at the slightest provocation, and he would turn on friends, dismissing them curtly as being unworthy of his friendship. But, likely as not, he would write a letter the next day or so, telling them how noble and good they were and how he had misjudged them.

Coaxing the “Wild Man” to Perform:

I have heard him play; but to bring him so far required some management, so great is his horror of being anything like exhibited. Had he been plainly asked to do the company that favour, he would have flatly refused; he had to be cheated into it. Every person left the room, except Beethoven and the master of the house, one of his most intimate acquaintances. These two carried on a conversation in the paper-book about bank stock. The gentleman, as if by chance, struck the keys of the open piano, beside which they were sitting, gradually began to run over one of Beethoven’s own compositions, made a thousand errors, and speedily blundered one passage so thoroughly, that the composer condescended to stretch out his hand and put him right. It was enough; the hand was on the piano; his companion immediately left him, on some pretext, and joined the rest of the company, who in the next room, from which they could see and hear everything, were patiently waiting the issue of this tiresome conjuration. Beethoven, left alone, seated himself at the piano. At first he only struck now and then a few hurried notes, as if afraid of being detected in a crime; but gradually he forgot everything else, and ran on during half and hour in a fantasy, in a style extremely varied, and marked, above all, by the most abrupt transitions. The amateurs were enraptured; to the uninitiated it was more interesting to observe how the music of the man’s soul passed over his countenance. He seems to feel the bold, the commanding, and the impetuous, more than what is soothing or gentle. The muscles of the face swell, and its veins start out; the wild eye rolls doubly wild, the mouth quivers, and Beethoven looks like a wizard, overpowered by the demons whom he himself has called up.

— John Russell —

A Tour in Germany, and Some of the Southern Provinces of the Austrian Empire, in 1820,1821,1822,1828

Deafness:

Beethoven’s career as a virtuoso pianist was brought to an end when he began to experience his first symptoms of deafness. In a letter written to his friend Karl Ameda on 1 July 1801, he admitted he was experiencing signs of deafness.

How often I wish you were here, for your Beethoven is having

a miserable life, at odds with nature and its Creator, abusing

the latter for leaving his creatures vulnerable to the slightest

accident … My greatest faculty, my hearing, is greatly

deteriorated.

Apparently Beethoven had been aware of the problem for about three years, avoiding company lest his weakness be discovered, and retreating into himself. Friends ascribed his reserve to preoccupation and absentmindedness. In a letter to Wegeler, he w rote:

How can I, a musician, say to people “I am deaf!” I shall, if

I can, defy this fate, even though there will be times when I

shall be the unhappiest of God’s creatures … I live only in

music … frequently working on three or four pieces simultaneously.

Many men would have been driven to suicide; Beethoven may indeed have contemplated it. Yet his stubborn nature strengthened him and he came to terms with his deafness in a dynamic, constructive way. In a letter to Wegeler, written five months after the despairing one quoted above, it becomes clear that Beethoven, as always, stubborn, unyielding and struggling against destiny, saw his deafness as a challenge to be fought and overcome:

Free me of only half this affliction and I shall be a complete,

mature man. You must think of me as being as happy as it is

possible to be on this earth – not unhappy. No! I cannot endure

it. I will seize Fate by the throat. It will not wholly conquer

me! Oh, how beautiful it is to live – and live a thousand times over!

With the end of his career as a virtuoso pianist inevitable, he plunged into composing. It offered a much more precarious living than that of a performer, especially when his compositions had already shown themselves to be in advance of popular taste . In 1802 his doctor sent him to Heiligenstadt, a village outside Vienna, in the hope that its rural peace would rest in his hearing. The new surroundings reawakened in Beethoven a love of nature and the countryside, and hope and optimism returned. Chief amongst the sunny works of this period was the charming, exuberant Symphony no. 2. However, when it became obvious that there was no improvement in his hearing, despair returned. By the autumn the young man felt so low both physically and mentally that he feared he would not surive the winter. He therefore wrote his will and left instructions that it was to be opened only after his death. This ‘Heiligenstadt Testament’ is a long moving document that reveals more about his state of mind than does the music he was writing at the time. Only his last works can reflect in sound what he then put down in words.

O ye men who accuse me of being malevolent, stubborn and

misanthropical, how ye wrong me! Ye know not the secret

cause. Ever since childhood my heart and mind were disposed

toward feelings of gentleness and goodwill, and I was eager

to accomplish great deeds; but consider this: for six years

I have been hopelessly ill, aggravated and cheated by quacks in

the hope of improvement but finally compelled to face a lasting

malady … I was forced to isolate myself. I was misunderstood

and rudely repulsed because I was as yet unable to say to people,

“Speak louder, shout, for I am deaf” … With joy I hasten to meet

death. Despite my hard fate … I shall wish that it had come later;

but I am content, for he shall free me of constant suffering. Come

then, Death, and I shall face thee with courage. Heiglnstadt (sic)

6 October, 1802.

Just how bad was Beethoven’s plight? At first the malady was intermittent or so faint that it worried him only occasionally. but by 1801 he reported that a whistle and a buzz was constant. Low speech tones became an unintelligible hum, shouting became an intolerable din. Apparently the illness completely swamped delicate sounds and distorted strong ones. He may have had short periods of remission, but for the last ten years of his life he was totally deaf.

After Heiligenstadt:

After his return from Heiligenstadt, Beethoven’s music deepened. He began creating a new musical world. In the summer of 1803 he began work on his Third Symphony – the ‘Eroica’. It was to be the paean of glory to Napoleon Bonaparte and like its subject, it was revolutionary. It was half as long as any previous symphony and its musical language was so uncompromising that it set up resistance in its first audiences. It broke the symphonic mold, yet established new, logical and cogent forms. This was the miracle Beethoven was to work many times.

Stephan von Breuning, with whom Beethoven shared rooms, reports a thunderous episode in connection with the ‘Eroica’ Symphony. In December, 1804, the news arrived that Napoleon, that toiler for the rights of the common people, had proclaimed himself Emperor. In a fury, Beethoven strode over to his copy of the Symphony, which bore a dedication to Napoleon, and crossed out the “Bonaparte” name in such violence that the pen tore in the paper. “Is he, too, nothing more than human?” he raged. “Now he will crush the rights of man. He will become a tyrant!”

For the next few years in Vienna, from 1804 to 1808, Beethoven lived in what might be described as a state of monotonous uproar. His relationships suffered elemental rifts, his music grew ever greater, and all the time he was in love with one women or another, usually high-born, sometimes unattainable, always unattained. he never married.

His Fifth and Sixth Symphonies were completed by the summer of 1808. The Fifth indeed takes fate by the throat; the Sixth (Pastoral) is a portrait of the countryside around Heilingenstadt. These and other works spread his name and fame.

In July 1812 Beethoven wrote a letter to an unidentified lady whom he addressed as The Immortal Beloved. It was as eloquent of love as his ‘Heiligenstadt Testament’ had been of despair. The following is a summary of the letter (follow the above link for more):

My angel, my all, my very self – a few words only today, and

in pencil (thine). Why such profound sorrow when necessity

speaks? Can our love endure but through sacrifice – but through

not demanding all – canst thou alter it that thou art not wholly

mine, I not wholly thine?

So moving an outpouring may well have resulted, at last, in some permanent arrangement – if the lady in question had been free, and if the letter had been sent. It was discovered in a secret drawer in Beethoven’s desk after his death.

His brother Casper Carl died in November 1815. The consequences brought about something that neither the tragedy of deafness nor Napoleon’s guns could achieve: they almost stopped Beethoven composing. Beethoven was appointed guardian of his brother’s nine-year-old son, Karl – a guardianship he shared with the boy’s mother Johanna. Beethoven took the appointment most seriously and was certain that Johanna did not. He believed her to be immoral, and immediately began legal proceedings to get sole guardianship of his nephew. The lawsuit was painful and protracted and frequently abusive, with Johanna asserting “How can a deaf, madman bachelor guard the boy’s welfare?” – Beethoven repeatedly fell ill because of the strain. He did not finally secure custody of Karl until 1820, when the boy was 20.

The Ninth Symphony (Choral) was completed in 1823, by which time Beethoven was completely deaf. There was a poignant scene at the first performance. Despite his deafness, Beethoven insisted on conducting, but unknown to him the real conductor sat out of his sight beating time. As the last movement ended, Beethoven, unaware even that the music had ceased, was also unaware of the tremendous burst of applause that greeted it. One of the singers took him by the arm and turned him around so that he might actually see the ovation.

His Death:

In the autumn of 1826, Beethoven took Karl to Gneixendorf for a holiday. The following is an account of Beethoven the possessed genius as he worked upon his last string quartet:

At 5:30 A.M. he was at his table, beating time with hands

and feet, humming and writing. After breakfast he hurried

outside to wander in the fields, calling, waving his arms about,

moving slowly, then very abruptly stopping to scribble

something in his notebook

In early December Beethoven returned to Vienna with Karl and the journey brought the composer down with pneumonia. He recovered, only to be laid low again with cirrhosis of the liver, which in turn gave way to dropsy. His condition had deteriorated dramatically by the beginning of March and, sensing the worst, his friends rallied round: faithful Stephan brought his family and Schubert paid his respects.

Beethoven’s final moments, if a report by Schubert’s friend Huttenbrenner are to believed, were dramatic in the extreme. At about 5:45 in the afternoon of 26 March, 1827, as a storm raged, Beethoven’s room was suddenly filled with light and shaken with thunder:

Beethoven’s eyes opened and he lifted his right fist for

several seconds, a serious, threatening expression on

his face. When his had fell back, he half closed his eyes

… Not another word, not another heartbeat.

Schubert and Hummel were among the 20,000 – 30,000 people who mourned the composer at his funeral three days later. He was buried in Wahring Cemetery; in 1888 his remains were removed to Zentral-friedhof in Vienna – a great resting place for musicians – where he lies side-by-side with Schubert.